Love, Unbroken

March 2015

We found ourselves driving through chaotic city traffic again a week after Bren’s last clinic appointment, the quickest turnaround so far between appointments. We were frustrated by the bumper-to-bumper traffic before we even reached the clinic. I looked in the revision mirror to check on Bren. Sitting in the back, he had more room to get his leg into a comfortable position. His eyes were closed; I could tell he wasn’t sleeping. He was trying to manage the pain with his mind. The meds were still barely taking the edge off. I heard on the radio that search crews had found the first of two black box recorders from the airliner that crashed in the French Alps on Tuesday. Horrifically, six crew members and 144 passengers were killed. My heart broke for their families and the lives lost. And for us. What if someone on that plane had the cure for undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma in the future they no longer have?

Bren’s first appointment in the city was with Dr. Brach’s registrar. We were scheduled to meet with Dr. V and Dr. Brach the following day. Wednesdays were always busy in the Bone Clinic. We left Bren’s wheelchair near the reception desk and made our way carefully to two seats together at the back of the waiting room. Bren looked pale, his jaw clenched against the pain radiating through his body—using crutches only made it worse. I didn’t know how he was going to cope with the PET scan he needed before those next appointments.

The PET results came through while we were with Dr.V the following afternoon. He looked at the computer screen for several minutes before sharing the results with us. I knew by the look on his face that we were about to step onto the cancer rollercoaster again. He closed his eyes in a slow, determined blink, the kind of blink you take when you see something you don’t want to see. He took a breath, turned back to look at us, and delivered the news: the scans showed confirmation the lump was a symptom of reoccurrence. Undetectable satellite cancer cells in the soft tissue around where the tumour was removed had caused a new growth. The cancer had returned. It was no longer contained within the bone. Dr. V suggested the most effective course of action in the gentlest way possible. The mere mention of limb removal devastated us; the shock at the prospect rendered our worst fears into a surreal reality too awful to bear.

Summoning his strength, Brendan paused, weighing options: amputate—live, don’t amputate—die. It should have been an easy decision to make. It wasn’t. Understanding the severity of tumour-related pain, Dr. V again suggested emergency admission to Princeton for pain management until Dr. Brach confirmed the operation date. Dr. V also assured Bren he could help him manage his pain at home with the help of our GP if Bren thought he could cope with it, knowing he would want to get back to the kids.

Bren wanted to be the one to tell them what was about to happen and help them through this next devastating turn of events. He didn’t want to be apart from them for however long it would take to schedule the operation.

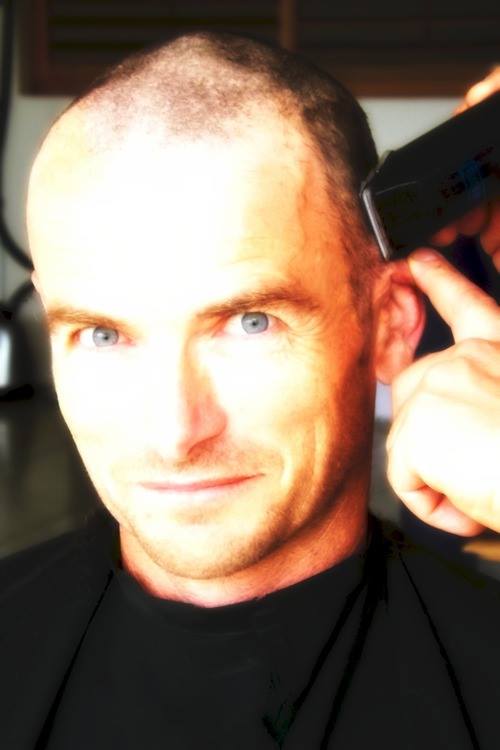

The following day, as we made our way home, without knowing, Bren’s work colleagues had organised a shave for a mate day attended by family, friends, workmates, and our ever-supportive community. This act of kindness lifted Bren when he needed it most. They didn’t know yet that the cancer had returned but suspected he was in trouble again. A volunteer hairdresser shaved many heads and beards (one that had been growing for almost 25 years) that day. Alongside the boys that stepped up was my sister Deb, who had gorgeous sandy blonde, waist-length hair, and Kim, a longtime family friend and wife of one of Bren’s good mates, Greg; Kim’s blonde bob fell just below her shoulders. Bald heads and freshly shaved faces were beautiful on every one of them, and thousands of dollars were raised.

Fast forward to Saturday. It was late afternoon, and our kids were swimming at Deb and Andy’s house when Dr. Brach rang to discuss Bren’s treatment options. The multidisciplinary team, consisting of his oncologist, orthopaedic surgeon, radiologist, cardiothoracic surgeon, and I suspect a physiotherapist, occupational therapist, social workers, and nursing staff, have worked on a personalised treatment plan for Bren since his diagnosis. I don’t know who or how many review Bren’s case in the meetings. I assume all the big players attend. I’m sure it’s no small feat to bring them together, but they managed to do it regularly; the team concluded that the most curative course of action for Brendan now was limb removal. Dr. Brach was available to do the surgery if that was the course of action Bren wanted to take.

Seeking a second opinion would be supported, with all files available and sent wherever needed. Time, though, was of the essence. Dr. Brach gave Bren his private mobile number so there would be no delay if he decided to proceed with the operation; the ball was now in Bren’s court. He had the most unimaginable, heart-wrenching decision to make; he had to make the call to have his leg removed.

Before tapping Dr. Brach’s number into his phone, Bren lay on the floor for almost an hour; he knew what he had to do, but pushing those numbers into the phone at that moment seemed more difficult than pushing a broken-down kombi up a hill. Tears were running from the corners of his eyes and pooling in his ears. He let the phone slip from his hand as he rested his other arm across his eyes and cried. I lay on the floor beside him.

“You don’t have to do this now,” I said, trying to comfort him.

“Yeah, I do.” He replied, still crying.

It’s not an easy thing to do; ring someone and arrange for them to cut your leg off. Not even when your life depends on it, but he did. Dr. Brach was in his backyard enjoying some much-deserved downtime on a sunny Sunday morning when Bren finally punched his number into the phone and asked him to schedule the amputation.

Now, we had to tell our kids what would happen next. They had spent the morning at Aunty Deb and Uncle Andy’s house with Luca, Tyler and my Mum and Dad so we could first break the news to Bren’s Mum and Dad. The kids came home after lunch and played with their friends in the street; we called them inside earlier than usual to let them know the plan. We had told them their dad losing his leg was a possibility a couple of nights before, and they had both cried their little hearts out. I am sure Bren’s heart was pounding out of his chest, just like mine, as he took in a deep breath and told them after a long discussion with Dr. Brach on the phone, Dad was going to take Dr. Brach’s advice and have his leg amputated to get rid of the cancer.

Bades cried as he threw his arms around Bren’s neck, not wanting to let his dad go. Tyz looked up at Bren from where she was sitting with me at his feet and said through tears,

“You know what, Dad? I’m not going to be scared of rollercoasters anymore!”

As hard as it was, we focused on keeping as much laughter in the house as possible in the following days. The kids came home from school the day after we broke the news to them, and at some point, the first one-legged joke surfaced between the four of us, which had us all in fits of laughter.

Dr. Brach rang to confirm Bren’s operation date for the amputation precisely one week before the event. It was the first time in Brendan’s cancer treatment and recovery that I saw real fear in his eyes. It came with a guttural, almost primal cry he had been holding on to as he hung up the phone. His fear intensified as he confronted the reality that he was about to lose his leg. His cry was a release of indescribable physical and emotional pain. We would both shed tears together and separately many times in the days to come. Grief hits you in unexpected ways and at random moments. We grieved this loss deeply as we prepared for the surgery ahead while trying to manage Bren’s pain.

March 30, 2015

It has been the shittiest of times; although we have become accustomed to Bren’s bum shuffling around the house, it is more difficult for him now. We have been back and forth to our GP to increase his medication dosage since our last trip to the city. We can’t seem to reduce Bren’s pain to a manageable level, no matter how many adjustments Dr. Chris makes to the dosage. The pain increases every day. Dr. Chris has permitted Bren to take Endone as often as he needs as breakthrough support between doses of Targin. Targin is a modified-release tablet that combines oxycodone and naloxone. The naloxone component helps with opioid-induced constipation. Bren’s tumour pain is so extreme he won’t overdose on the high drug doses he has to take. The medication regime is an intricate dance; I had no idea how essential bowel movements are to our overall well-being until I had to start monitoring Bren’s, as the heavy drug dosages messed with his system. He got sick of me constantly asking him if he’d pooed.

When all else fails, and Endone isn’t helping cover between Targin doses, I can soothe him a little, emotionally more than physically, by sharing the warm Reiki energy coming from my hands as I gently lay them on his leg where the pain is most extreme. We do this for hours through the night, Bren sobbing silently until exhaustion brings fitful sleep and a little respite. It’s become a nightly routine. Sleep doesn’t find me often on the worst nights. Instead, I continue running gentle energy into my husband’s body as he flinches and groans in his sleep until he wakes, and it starts all over again.

I loved everything about Bren, including his right leg. Knowing that it would be gone in just seven days broke my heart. I couldn’t stop wondering what would happen to it after the amputation. I hoped it would be treated with dignity and respect. Bren was losing a huge part of himself, and the thought of his leg being carelessly discarded felt unbearable. I chose not to ask what would become of it; the answer might be one I couldn’t live with.

The afternoon before the operation, Bren had his first call with Michelle, the amputee consultant. Talking about his amputation before it happened was essential, but it felt strange. Everything about cancer is strange. A conversation about amputation relating to my husband wasn’t one I imagined ever having. Still, here we were, on speaker, talking about shrink socks, the difference between above-the-knee and below-the-knee amputation, and the challenges an above-the-knee amputee might face. Especially while undergoing chemotherapy, as the pain of the tumour causing the amputation was crushing him.

After the call, we sat on the bed in our hotel room, and I hugged Bren’s leg gently to my chest while I gave him a Reiki treatment to soothe the pain around the lump. I could feel the weight of his leg and the tumour pressing against me. Soon, it would be gone. Brendan’s leg would be gone, and so would the tumour. That realisation was bittersweet.

March 31, 2015

The morning of Bren’s operation came around fast, thankfully, as the days leading up to it were horrendous. At one point, in the middle of an intense bout of pain, just days before, he said through clenched teeth, “Only a couple of days to go, only a couple of days to go.” When I heard Bren say that I wanted to throw up, knowing at that moment, for him, his leg being gone was better than the pain he was in. I couldn’t wait for it to stop. I never wanted to see him suffer again.

Sue and Mike had taken a week off work to support us and met us in the hotel’s basement car park at 6:15 on the morning of the operation. The hospital’s preoperative centre was not even a full block up the road, but we would not have made it without a car. Bren’s pain was so severe now he had to get out of his wheelchair and lay down on the grimy car park floor to wait the few minutes they were behind us in the next lift. We were at the desk in Perioperative by 6:30am, not knowing what time the nurse would call Bren for his operation; I asked if she could organise a gurney for him.

The nurse asked the receptionist to check Bren’s operation schedule. She pulled his file and, on the front, a red card reading Priority Case Dr. Brach, in large black type, was attached with a paper clip. “Oh!” she said, “Brendan’s up first. We can put him on a gurney now, or he can sit for a few minutes until the nurse calls him in if you think he can manage.”

“He can’t,” I said. He got a gurney.

We said our heart-wrenching goodbyes and watched as Bren was wheeled away on a gurney by an orderly. Sue, Mike, and I then made our way upstairs to the hospital café for breakfast. And who should be sitting there with two colleagues? Bren’s surgeon. He was in the building and looked well rested. I was relieved. As he stood to leave, carrying an armful of files, likely Bren’s—Mike called out, “Have a good day, guys.” The doctors turned in our direction. Sue added, “You look after our Brendan.” Dr. Brach gave us a warm smile and replied. “I’ll do my best.”

His best was the best in the country. My husband was in good hands. Waiting for Bren to come out of recovery was excruciating. It didn’t help that I didn’t know how long the operation would take. By 11am I couldn’t wait any longer, I rang the number given at reception to find out what ward Bren would be returning to. Nobody at that number seemed to know where he was or how much longer he would be. On the next call, I got the ward number, but Bren was still in recovery, waiting on a bed. So, we made our way up to the ward waiting room, and I checked in with the nurse at the desk regularly to see if he was back. I’m sure she groaned a little every time she saw me coming, but she was very kind to me.

Finally, just after 1:30 pm, a nurse called, “Saunders!” My sister Deb’s married name. I half jumped up and said, “Yes…um, no!” we all laughed. Not long after, the nurse returned and called, “Maloney!” I hadn’t moved that fast in a long time.

I walked into Bren’s room and quietly pulled the curtain back. He had the faintest trace of a tear in the corner of his eye as he smiled at me, but he looked good. It was all I could say, “You look good, you look so good.” Yes, it was obvious that his leg was gone, and it was weird, and we both agreed that it was weird, but he was still Bren, and the lightness in his face was beautiful. We hugged and kissed, and like I have done every day for the last six weeks and more, I put one hand on his heart and one hand on his leg where the bandages were and let warm, tingly energy flow between us. And we both took a breath. Bren told me that he had woken from the anaesthetic crying and didn’t know why until he realised, he wasn’t in unbearable pain for the first time in two months.

After we spent a little time together, I asked if he was ready to see his Mum and Dad, who had arrived in the city the day before. I knew how anxious they were to see him. He said, “Juice me up for a little bit longer,” which meant more Reiki first. Reiki has a calming, comforting effect, and he needed some extra support now to help his Mum and Dad handle what they were about to experience. We knew seeing him without his leg for the first time would be tough for them.

Margaret and Len willed themselves to be strong and took strength in each other as I walked with them into Bren’s room. They were terrific, and I know it was shocking for them. There were some quiet tears as they embraced him as only his parents could.

Bren’s sister Elle was next, followed by Sue and Mike. Day one was nearly over, and six of Bren’s nearest and dearest had stepped with him into his new world; it wasn’t easy for any of us, but Bren’s strength and courage got us across the line. Sue, Mike, and I stayed until visiting hours were over. It was a long day that changed the direction of our lives. It was hard to say goodnight and leave him there alone.

I had felt Ok all day. As Sue, Mike and I waited for the elevator, Sue looked at me and said: “Are you OK?” I heard myself say, yes but could feel an overwhelming surge of grief and heartbreak moving violently through me as I collapsed into their arms, sobbing uncontrollably. As they held me up, I was aware of the lift door opening and closing because I kept pressing the button. I wanted to get into the lift so Bren, who was only two rooms away, couldn’t hear me crying.

April 1, 2015

After a drowsy day, recovering from the anaesthetic and coping with a good cocktail of drugs, tonight Bren was wide awake, clearer-headed, and his spirits were high. Considering what he’d been through and the shock his body must have been in, it was a good sign that his recovery would go well. The nurse looking after him let me stay past visiting hours, which I was grateful for, because I got to see Bren sit upright and lift his bum off the bed using his arms and left leg, and he did it several times. His nurse was impressed, hardly having to help him. Lifting himself into a sitting position took a lot of energy and effort. He also had to work out his balance and coordination since almost a quarter of his body was missing. But he wanted me to see him do it before I left. All his tubes, drips, and drains are gone, and Dr. Brach is happy with how the operation went. Aside from a quick visit from the physiotherapist to start getting him up and about, tomorrow will be a day of rest.

I don’t know how I would have made it through the last few days without my sister Sue and our brother-in-law Mike; they barely left my side, constantly supporting Bren and me. My sister Deb, brother-in-law Andy, and their four kids have been Godsends, too, looking after our kids back home, so we didn’t have to worry about them. We knew Tyz and Bades were safe and happy. And Aunty Deb and Uncle Andy made sure the Easter Bunny found them. We will never forget what they have done for us.

Leave a comment